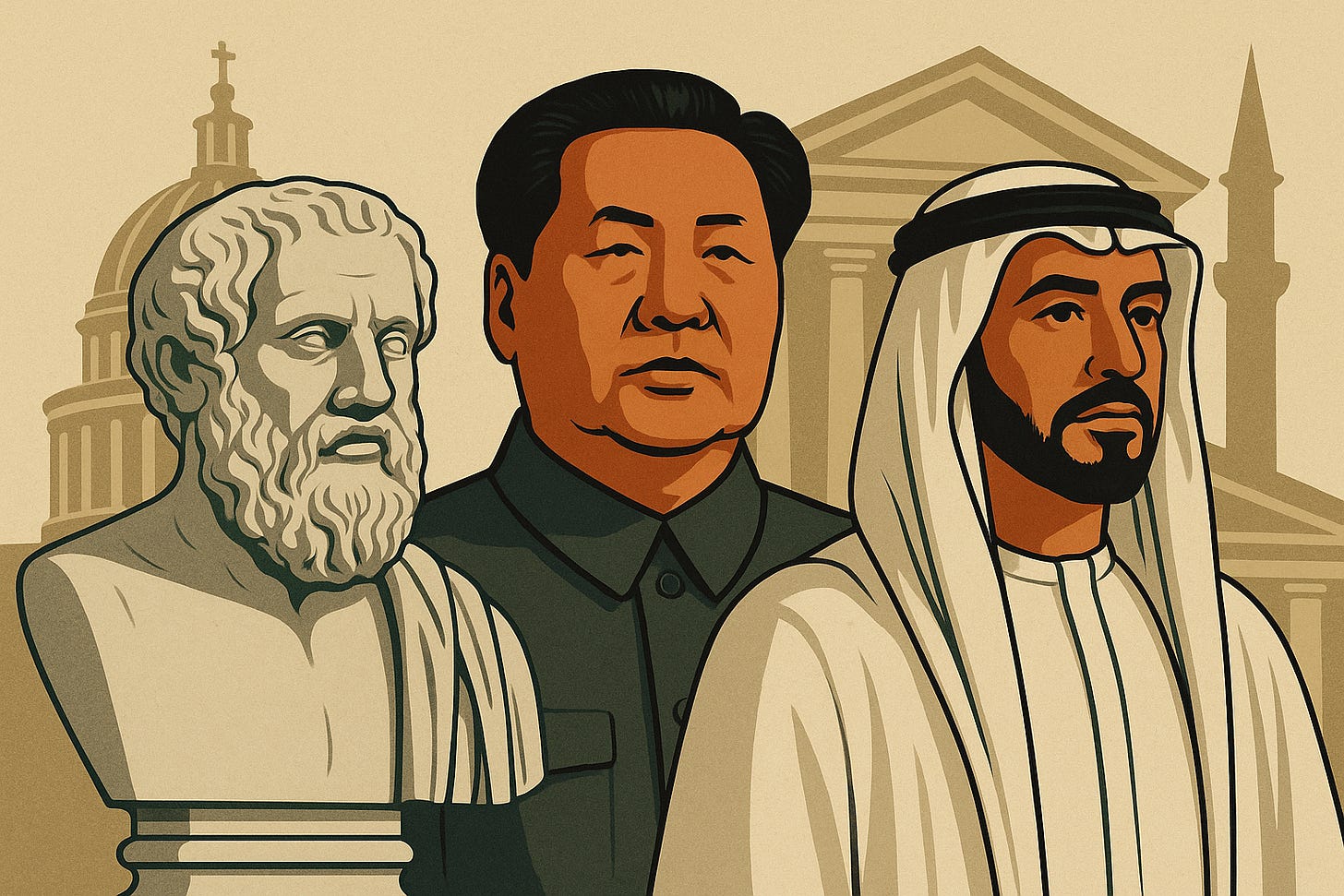

I read with great interest “The Need for Civilizational Allies in Europe” published with ’s substack, released two weeks ago. A cornerstone logic underpinning the argument is interesting because it mirrors the rhetoric that China and other states like Iran use as a form of “civilizational diplomacy”. Uniquely, I was writing a substack post for separately evaluating China’s use of this approach to build bridges with the global south, most recently the Arab world. Seeing this narrative also emerging from the Department of State, I wanted to dig a little bit deeper.

An argument for a U.S. alliance grounded in “civilizational values,” as presented signals a troubling revival of Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thinking. This worldview—based on the assumption that religion and culture are the primary structures of global politics—offers a clean narrative but a dangerous foundation for foreign policy. Civilizational diplomacy doesn’t clarify America’s strategic vision—it distorts it. And worse, it risks marginalizing U.S. partners who are central to advancing U.S. foreign policy and national security interests.

Framing alliances around “Western civilization” rather than shared interests creates a hierarchy of belonging and, potentially, exclusion. Countries like Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia may cooperate closely with Washington—but under this rubric, they will always be “outside” the core alliance. This is both diplomatically shortsighted, alienating to important partners, and creates unnecessary gaps with partners already concerned of U.S. retrenchment in the Middle East and shifting priorities toward China. This approach divorces a hard realist assessment of U.S. foreign policy rooted in interests, needs, and capabilities. Instead, it offers a a civilizational schema predicated on broad assumptions about culture and religion as fixed, organizing forces. That may be seductive to those longing for clarity in global affairs—but it collapses under the weight of complexity and interdependence.

Ironically, this approach also undermines Trump’s own record in the Middle East. His administration advanced diplomacy through interests, not cultural litmus tests. His speech in Saudi Arabia was dripping with rhetoric abandoning the pursuit of ideological-based foreign policy. From the Abraham Accords to energy cooperation, Trump’s team engaged regional partners based on shared goals and strategic alignment—not civilizational identity. This rhetoric introduces an unnecessary barrier between the U.S. and its most cooperative Middle Eastern allies. Likewise, it risks repeating the Biden administration’s mistake with the Summit for Democracy, which imposed a narrow ideological filter and excluded many key U.S. partners. The Though it rightly aimed to elevate democratic norms, the result was exclusion and confusion in practice. Civilizational diplomacy would replicate this problem on a broader, more permanent scale, replacing ideological conformity with cultural essentialism.

The article also raises alarm about the weaponization of state institutions to silence dissent and curtail free speech in parts of Europe. But the critique loses credibility when it treats this as a uniquely European or civilizational crisis. The same U.S. administration promoting this narrative has targeted civil society at home, investigated political opponents, targeted judges, and challenged the legitimacy of rule of law, and leveraged government tools to chill speech in the name of protecting it. These aren’t isolated to one culture or continent. They are structural symptoms of democratic erosion. The answer isn’t to wrap these concerns in the flag of Western exceptionalism. Rather, they must be confronted with institutional accountability, legal restraint, and a recommitment to pluralism. Free speech is not safeguarded by civilizational rhetoric—it’s protected by practice. And it seems globally that practice is far from present. The author may believe the pendulum swung too far in one direction, but pushing too far in the opposite direction virtually the same action.

The article also leans heavily on a selective reading of history—tracing Western virtue through an exclusive arc from Athens and Rome to Christianity and the American founding. This framing not only flattens the diversity of Western experience, but ignores the global intellectual ecosystem that shaped today’s democratic principles. Arab, Persian, and Islamic scholars preserved classical knowledge through the medieval period. Enlightenment ideas were shaped through encounters with—and reactions to—global empires and trade. Anti-colonial thinkers, post-colonial struggles, and movements from the Global South have all expanded the world’s understanding of freedom, rights, and law. To conflate liberty and virtue with one civilizational strand is not only historically narrow—it again alienates partners whose traditions contributed to the very American-led order the author claims to defend.

We also see this dynamic also plays out in China’s foreign policy rhetoric. Beijing has pursued its own brand of “civilization diplomacy,” branding itself as a natural partner to ancient cultures (the “5000 year old civilization narrative) and “non-Western” nations. This strategy has helped it deepen ties with countries like Iran and Egypt by promoting a shared narrative of historical continuity and resistance to Western dominance. But it has also hardened divides, excluded outliers, and fostered geopolitical blocs built on identity rather than shared goals. If the U.S. begins defining its alliances through the same civilizational logic, it will push more countries—especially in the Middle East—toward strategic neutrality and question the foundations of their ties with the U.S.

Proponents of civilizational diplomacy also claim to resist “globalism” in favor of moral clarity. But that’s a false choice. Global engagement does not require globalist conformity. The U.S. can defend pluralism, religious freedom, and sovereignty without dividing the world into fixed cultural camps. Durable coalitions aren’t built on shared bloodlines or moral threads—they are built on shared action. We should speak in terms of strategic alignment, institutional resilience, and mutual problem-solving—not cultural lineage.

Reviving Huntingtonian logic may offer rhetorical coherence in a snappy substack article, but it fails as strategy in foreign policy, whether the U.S. or China. It reduces diverse societies to monolithic blocs and frames diplomacy as a contest of identities, rather than a negotiation of interests. That’s a dangerous mistake in a moment when global power is already fragmenting. Both the Trump and Biden administrations, in different ways, have shown the risks of ideology-first diplomacy. Civilizational diplomacy risks repeating the worst of both. It alienates the Global South, sidelines the Middle East, and hands China a justification to double down on its own identity-based narrative.

We should not ask who shares our histories. We should ask who shares our willingness to act. Identities can be redefined—as can histories—but how states choose to interact, and what they choose to pursue together, sets the stage for a more stable and cooperative future.