From Mecca to Chang’an

Islam's Westward Expansion

This paper explores the formative diplomatic interactions between the emerging Islamic civilization and China’s Tang Dynasty in the 7th century.

The 7th century CE marked transformative periods for both the Arabian Peninsula and East Asia. As the Arab empire solidified control across Arabia under Muhammad, establishing itself as a dominant religious and political entity, the Tang Dynasty in China concurrently embarked on its golden era of westward expansion.

Central to the confluence of these two empires was the Silk Road, the ancient network of trade routes. Beyond facilitating the exchange of tangible commodities like silk and spices, it served as a conduit for the transmission of ideas, knowledge, and religious beliefs, thereby catalyzing unique cultural amalgamations.

Chinese historians documented early diplomatic missions from the Islamic world venturing into China. A particularly notable delegation arrived during the reign of Emperor Gaozong. This delegation not only symbolized deepening trade interests but also reflected the intent of propagating a nascent faith.

Chang’an, the vibrant capital of the Tang Dynasty, became a melting pot of various cultures during this era. From Persian merchants to Indian scholars, and from Turkic warriors to Arab traders, each contributed to a rich cultural milieu. Within this dynamic setting, Islam began crafting its narrative, gradually finding acceptance and resonance.

These interactions were not just diplomatic or transactional. They led to a profound cultural exchange that left an indelible mark on both civilizations. Arabic inscriptions adorned Chinese artifacts, while tales of the enigmatic East became a staple in Arab travelers' chronicles. Among the most profound outcomes was the fusion of Arabic astronomy with indigenous Chinese celestial studies.

The Rashidun Visit to China

Since the founding of Islam and the subsequent expansion by Arab tribes, Islam has had a sustained presence in China. Traditional accounts suggest that the roots of Islam in China trace back to the decades following Muhammad's death in 632 CE. Legend has it that four companions of the Prophet journeyed to ancient China, preaching Islam. Uthman, the third caliph of the Rashidun, is believed to have dispatched an ambassador to Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty. In honor of this diplomatic gesture and the Prophet Muhammad, Emperor Gaozong purportedly ordered the construction of the Huaisheng Mosque – China's first and among the world's oldest.

This ancient bond has entrenched Islam and the Arab conquests in China’s history, linking it to the Middle East as a pivotal hub of trade, culture, politics, and at intervals, conflict. During Islam's inaugural century, the Arab empire, first under the Umayyad and later the Abbasid Caliphates, initiated tangible engagements with China. While relations started amicably, the eastward expansion of the Arab Empire eventually met the western frontiers of the Chinese realm in Central Asia.

The Battle of Talas: A Pivotal Moment in Sino-Islamic Relations

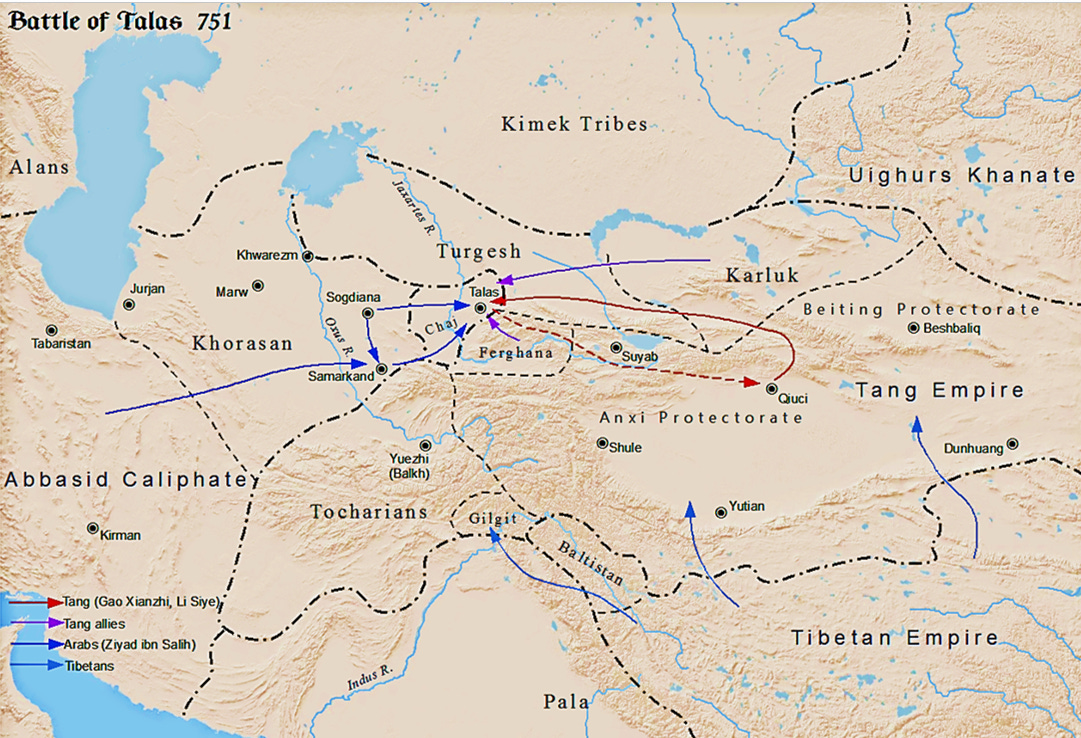

The Umayyad Empire, succeeding the Rashidun Caliphate, embarked on vast territorial campaigns during the 7th and 8th centuries. This expansion brought Arab armies deep into Central Asia, where they confronted numerous Central Asian nomadic tribes and settled communities. By the mid-8th century, the Umayyad's decline paved the way for the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Abbasid armies advanced to the very edges of the Tang Dynasty, culminating in the Battle of Talas in 751 CE.

Situated near the modern-day Kyrgyzstan's Talas River, this engagement saw the formidable Tang Dynasty pit against the formidable Abbasid Caliphate. This battle wasn't just a military contest; it became a defining moment for Eurasian geopolitics. The Tang, under its ambitious emperors, sought to extend its influence westwards, eyeing pivotal Silk Road trade routes. Conversely, the Abbasids, having solidified their hold over the Middle East and Central Asia, aspired to control the resource-rich Fergana Valley and to propagate Islam further.

The battle’s turning point arrived when the Qarluq Turks, initial allies of the Tang, defected to the Abbasid side. This significant shift determined the battle’s outcome and signaled broader political and ideological shifts in the region. The resulting Abbasid victory halted the Tang’s westward ambitions, marking a territorial boundary between the Islamic and Chinese realms that would persist for centuries.

However, the Battle of Talas' impact transcended territorial demarcation. Among the Tang prisoners taken were skilled papermakers, marking the inception of paper-making technology's westward journey, a boon that would profoundly influence the Islamic world's communication and scholarship.

Shared Innovations: Tracing the Paper Trail from China to the Islamic World

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of this engagement wasn't territorial, but the ensuing diffusion of knowledge and technology. Captured Tang artisans became unwitting ambassadors of innovation, heralding a mutual intellectual era. Prominent among the shared innovations was paper-making.

Post-Talas, Tang papermakers, now Abbasid captives, introduced this art. Recognizing its transformative potential, the Abbasids integrated paper into their vast domain. This shift from parchment and papyrus streamlined knowledge dissemination, empowering scholars in hubs like Baghdad to replicate texts more effectively.

The ensuing Islamic Golden Age witnessed a surge in scientific, philosophical, and literary pursuits. Libraries, exemplified by Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, burgeoned, with paper playing a pivotal role in this intellectual renaissance. Moreover, the Islamic realm didn't just adopt this craft; they honed it. Innovations in pulping and watermarking, coupled with fine paper suited for calligraphy, transformed cities like Samarkand into paper-making meccas.

As Islamic territories grew, so did paper-making, migrating to North Africa, Al-Andalus, and eventually Europe. Thus, an invention birthed in the Han Dynasty's workshops became a transcontinental medium, enriching civilizations for generations.

For more reading:

James Carter’s When China collided with the Middle East. 2020.

Barry Hoberman’s “The Battle of Talas, ” Aramco World, 1982.

Catherine Put’s “The Battle of Talas,” via The Diplomat. 2016.