From 2018-2020, I made several expeditions into Jordan’s remote deserts to document lesser studied parts of its history.

Far from the Nabataean city of Petra or Jordan’s widely travelled Wadi Rum lies the Kingdom’s remote al-Harra desert, colloquially known in English as the “black rock desert”. A natural extension of the Jabal Suwaida volcano field, the region’s largely untraversable expanse consists of a sea of volcanic rocks which for millennia has protected and preserved one of Jordan’s lesser told histories—that of the Safaitic-speaking nomads who populated the desert regions stretching from southern Syria to northern Saudi Arabia and, as some have posited, the possible origin of the Arabic language. Over the course of two years, I ventured on various trips to explore a number of remote Safaitic sites across the al-Harra and document the many stories and images carved into the rocks across the desert.

A natural museum

Sitting around a campfire in 2019 in the Al-Harra, the eastern volcanic desert of Jordan, my traveling companions and I shared stories of our adventure, tragedy, hope, and humor amidst a backdrop of the remote desert landscape. The intense late spring heat set with the sun giving way to a windy, cold evening. The sky above was clear, every star could be seen, and the world around was still. Our objective, a multiday trip across the desert to document a number of potential neolithic settlement sites among the volcanic rock and photograph Safaitic inscriptions therein, brought us into contact the remote beauty of one of Jordan’s most beautiful gems. In the black hills around the camp site, the ghosts of the ancient Arab al-Safa, the inhabitants of the al-Harra, live on through the thousands of inscriptions in ancient Safaitic, hilltop settlements, lake-side cairns, and other signs of ancient communities which have yet to be discovered.

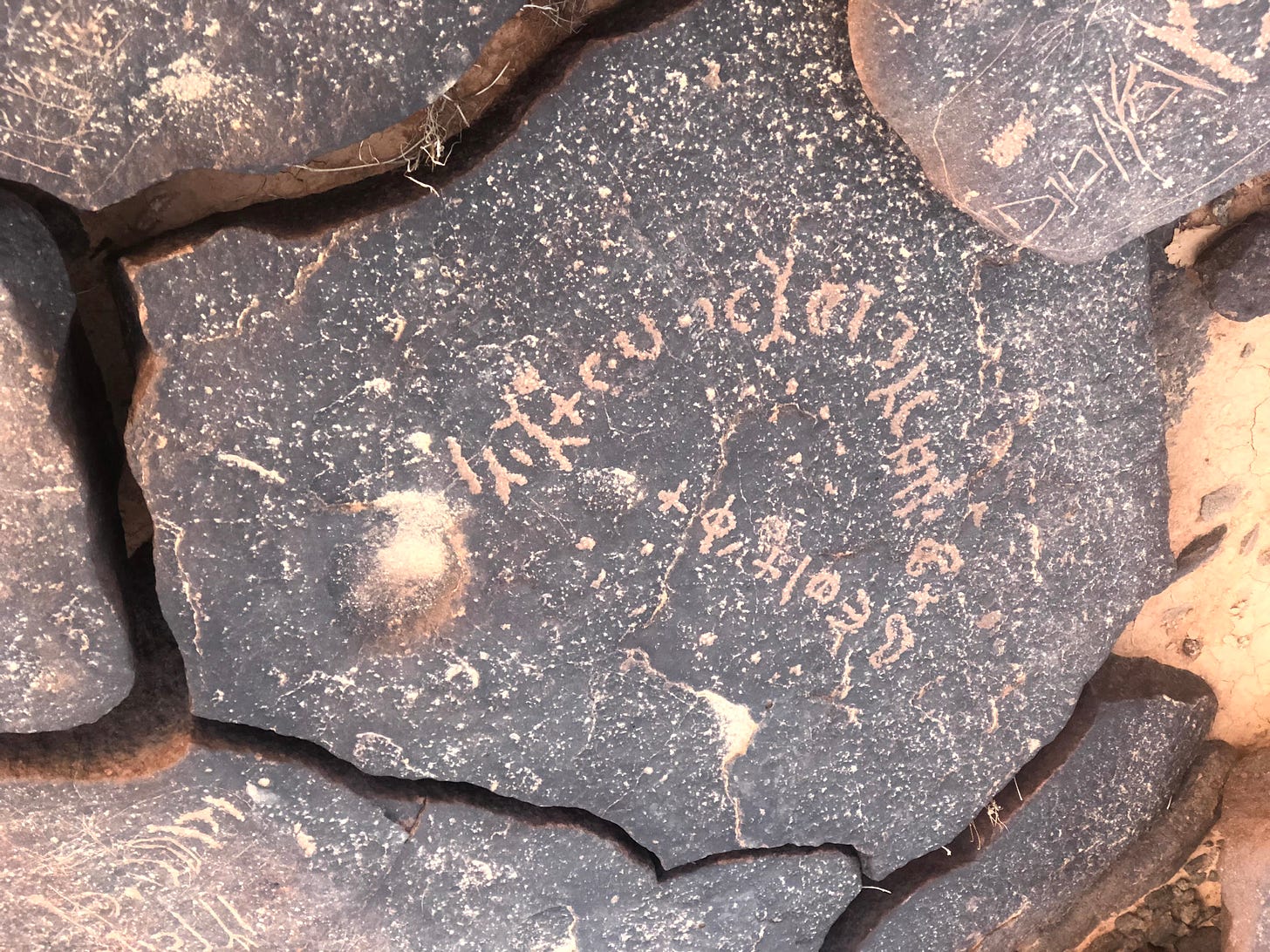

While the world around Al Harra has changed drastically, life in the Al-Harra desert remains largely the same. The thousands of accounts carved into the desert rocks by ancient watering holes, settlements, and animal hunting grounds—known as kites—detail day-to-day life for the ancient Safaitic speakers of the area. Alongside these ancient social media posts, the scars of centuries of history, conflict, war, development, modernization, climate change, and changing biodiversity remain.

Some 2000 years before we arrived to the remote Qa’a Albu Hussein, Honay’at bin Za’en, a nomad from northern Arabian desert, sat on a two-ton basaltic stone looking out over a seasonal lake with shores peppered with small ancient settlements. With a sharp piece of flint, he carefully carved his name into the dense, volcanic rock where it has been eternally memorialized in the timeless landscape. Nearby, another nomad, carved a prayer in stone asking for the ancient northern Arabian deity—Ruda—to grant him a camel as a spoil from a battle with the Hawilat, a northern-Arabian tribe often regards as an enemy of the Safaitic-speaking tribes. And, in another, Malqif, a nomadic animal herder and desert Picasso, carved into the face of a rock atop of large volcanic hilltop an image of a dog-like beast hunting a flock of now-extinct Arabian ostriches. Like the great European renaissance artists, Malqif signed his name in ancient Safaitic for his desert audience thousands of years later.

These stories are only a fragment of those we documented, and only a snapshot of the many thousand which have been collected and preserved. The work of leading scholars like Dr. Ahmadal-Jallad, Professor Jeremy Johns, as well as centers like the University of Oxford’s Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia (OCIANA), the Amman Museum, and the American Center for research (ACOR) have enabled the exploration, documentation, translation, and protection of these historic records for future generations to study.

From Roman to Ottoman

Beyond the region’s vast Safaitic inscriptions, the eastern desert has also witnessed the rise and fall of numerous empires, including the Roman, Umayyad, and Ottoman empires. During our travels across the desert, we saw a brief glimpse of their presence: In the 3rd century CE, the Romans built a fortress—Qasr Burqa—next to an ancient lake, whose water has sustained the consistent presence of human settlement for thousands of years.

The site later included the construction of a remote Byzantine monastery, followed by a Mamluk castle. Safaitic inscriptions can also be found along the shores of the lake and its surrounding areas. The ruins of Qasr Usaykhim, another prominent Roman castle, lies perched atop of a prominent hill overlooking the many water sources that populate the Azraq oasis, with signs of a number of smaller archaeological features dotting the distant hillsides.

The region’s rough, untraversable terrain also played an outsized role in the Great Arab Revolt, enabling the Arab forces, alongside T.E. Lawrence, to stage attacks against Ottoman forces from their stronghold of Azraq and its surround oasis. Looking from the sky, a century-year old road system was eternally etched into the desert, alongside a series of emergency runways carved in remote lake beds, by British military vehicles as a map for British pilots delivering mail from Cairo to Baghdad. Dotted along the edge of the Al-Harra, one can also find the remnants of forts, ancient and modern, which protected critical seasonal lakes which filled during the Spring rains, which were a lifeline and geostrategic position for ancient nomads and modern-era Ottoman military outposts.

Long-term, many of these sites could be important stops along Jordan’s forthcoming Eastern Badia Trail (JEBT), which aims to drive ecotourism eastward toward Jordan’s Azraq wetlands and wildlife reserves, and further into the al-Harra. The program aims to provide create employment opportunities for Bedouin who live in and around the region. The trail, however, remains on indefinite hold due to existing security challenges emanating from Syria.

Translating the Past for the Future

Jordan’s eastern el-Harra desert —far from Petra and Wadi Rum—is an understudied and underappreciated piece of the Kingdom’s unique history. Between modern conflicts and increasing desertification due to climate change, accessing these sites is growing more complicated. The region is remote and has limited traversable terrain for vehicles to navigate. Furthermore, cross border smuggling from Syria into Jordan has increased the risks of exploration in the regions in the border regions, where a large number of sites are concentrated.

As the Jordanian Armed Forces works to secure its border regions with Syria and build better infrastructure in the remote areas, Jordan has a unique opportunity to facilitate and partner with academic and research institutions to increase research expeditions to these areas to survey and document the many Safaitic sites in order to improve our understanding of this ancient region and its connection to Jordan’s modern history.

© Jesse Marks, Coffee in the Desert