Is China’s Global Security Initiative a viable alternative for GCC Security?

China’s Global Security Initiative (GSI), launched in April 2022, proposed a comprehensive framework for international security that prioritizes common, comprehensive, cooperative, and sustainable approaches. On paper, the GSI aligns with principles of mutual respect for sovereignty, adherence to the UN Charter, and peaceful conflict resolution through dialogue. However, the question remains whether the GSI can offer a viable alternative to existing security frameworks, particularly in the Middle East and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), where entrenched geopolitical rivalries and security dependencies make such a shift complex.

A Viable Alternative?

The GSI’s emphasis on a more inclusive security framework that respects regional sovereignty is undoubtedly attractive to countries in the Middle East, particularly as many regional states are concerned over the reliance on the U.S. in the region following a tumultuous decade of foreign policy. For decades, the U.S. has played the dominant role in regional security, particularly through military partnerships with GCC states aimed at deterring Iran. However, the GSI’s appeal lies in its promise to offer an alternative that avoids the entanglements it blames on the Western security architectures, such as the conditionalities tied to democracy promotion or human rights issues.

China’s GSI model is a double-edged sword. While China’s stance may be seen as more neutral and non-interfering, it may fail to address the realpolitik dimensions of Middle Eastern security, where alliances are often shaped by deep historical and ideological divides. The challenge for China will be balancing its desire to promote a cooperative security order without appearing to take sides in the region’s complex power struggles. Middle Eastern countries may find it difficult to embrace a security framework that does not explicitly align with their own security and political interests or that may seem to sidestep the region's humanitarian crises and governance concerns. China’s history - before 2023 - seemed to suggest a struggle to strategically balance between competing partners, notably Saudi Arabia and Iran. However, developments following China’s facilitating a Saudi-Iranian rapprochement suggest progress in Beijing’s own experience managing competing actors.

Mediation and Conflict Resolution

One of China’s strongest selling points in the GSI is its emerging role as a mediator in regional conflicts, highlighted by its involvement in restoring diplomatic ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran in 2023. This diplomatic coup marked a shift in regional dynamics, positioning China among Arab elites as a potential peacemaker in Middle Eastern disputes, a role traditionally held by the U.S. or, at times, regional actors themselves.

In January 2022, Foreign Minister Wang Yi - in a state interview - provided an in-depth overview of their proposed mechanism for mediating the GCC-Iran rift, and Beijing might build on this role.

“At present, the negotiations on resuming the implementation of the comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear issue are still ongoing. As one of the parties to the agreement, China is actively mediating to accumulate consensus. At the same time, we also understand the reasonable concerns of the Gulf countries on regional security. For this reason, China has specifically proposed the establishment of a multilateral dialogue platform in the Gulf region. We also invited experts and scholars from the Persian Gulf coastal countries to come to China to hold a "2-track" exchange to start the process of the initiative. In the next stage, China is willing to promote the implementation of the Gulf multilateral dialogue platform initiative as soon as possible on the basis of respecting the wishes of all parties, listening to the voices of all parties, and integrating the ideas of all parties, and hold a "1.5-track" forum meeting in due course, and gradually upgrade it to a government-level dialogue. Regional countries are invited to sit together in the spirit of ownership and bridge differences through frank dialogue. We suggest that we start with discussing the political solution of urgent regional hotspots such as Yemen, and gradually accumulate mutual trust from easy to difficult. When conditions are ripe, we can consider building a Gulf collective security mechanism to achieve common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable Gulf security.” -Wang Yi, translated from Mandarin.

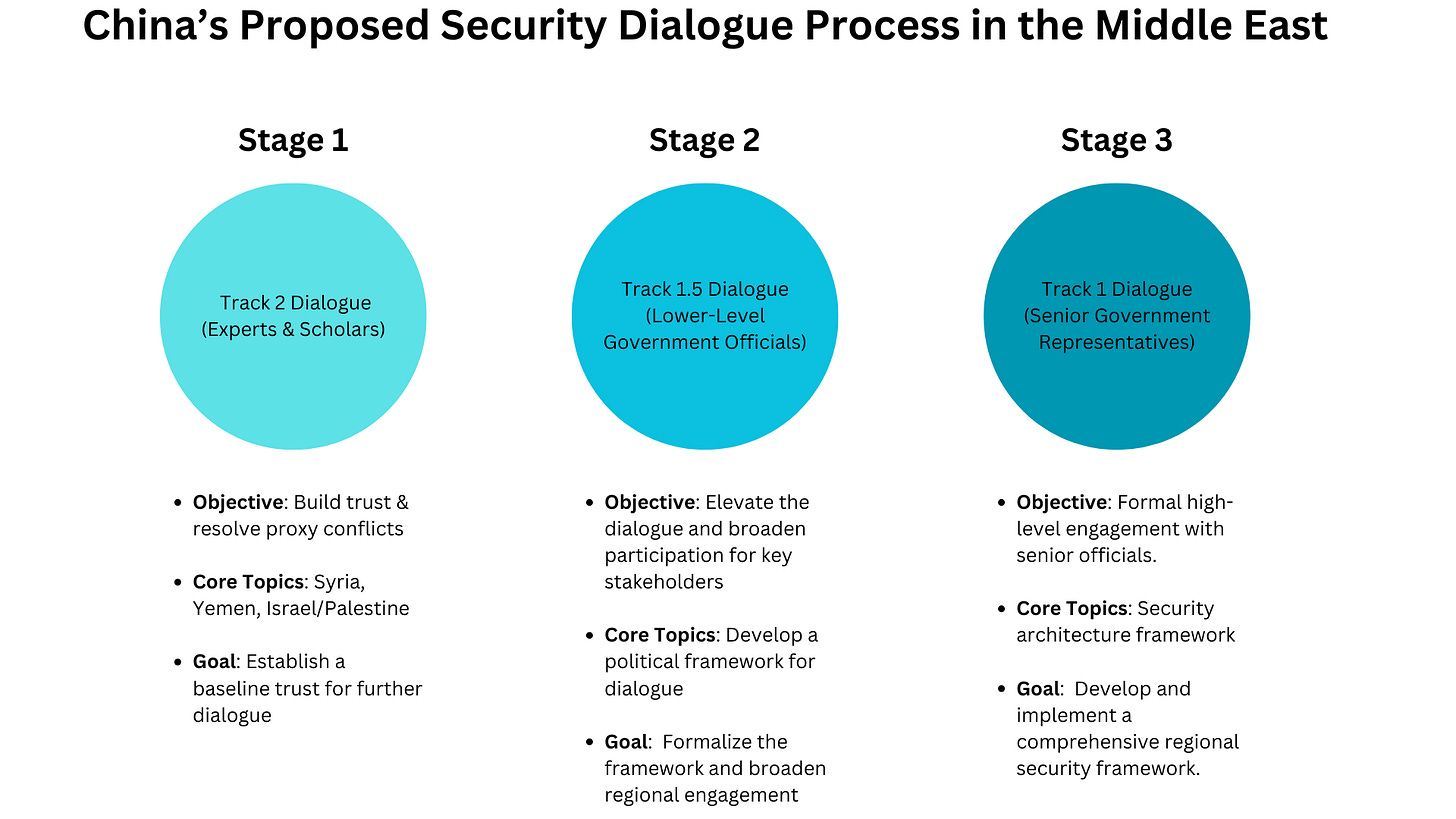

Below is an adapted process map I developed to visualize Wang’s proposal.

The first phase would bring together experts and scholars from Iran and Saudi Arabia in China for a track 2 exchange, aimed at building mutual trust and developing a shared framework for Gulf security. These discussions would focus on resolving proxy conflicts in Yemen and Syria, which are central to the Saudi-Iran rivalry. By addressing these conflicts early, the aim is to cultivate basic trust among the parties, setting the stage for further dialogue. This first phase would also allow Gulf countries to air their concerns and set conditions for advancing the process to higher levels of engagement.

Once this initial trust-building phase is successful, China would help elevate the dialogue to track 1.5, involving lower-level government officials, before moving to full track 1 discussions with senior government representatives.

Since 2023, Beijing has hosted two trilateral dialogues with Chinese, Iranian, and Saudi officials focused on improving bilateral ties based on the agreed-upon areas of focus. The most recent - in November 2024 - was held at the Deputy Foreign Minister level.

A key takeaway from this process is that Beijing’s incremental approach has the potential to facilitate genuine diplomatic breakthroughs, but its success depends largely on the willingness of competing parties to find common ground. While China has made strides in diplomacy, particularly in the Middle East, it has yet to prove its ability to mediate conflicts that are deeply entrenched in sectarian and ideological divisions, where mediation between unwilling parties is crucial for regional stability. The ongoing Gaza conflict is a prime example of such a situation. The real test for China will be whether it can maintain its neutrality while addressing the root causes of conflict, and whether it can secure the buy-in from all parties involved in the process.

Economic and Security Integration: The Belt and Road Dilemma

The GSI is also closely intertwined with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which focuses heavily in the Middle East on critical infrastructure, energy security, financing, investment, and trade. As a security initiative, the GSI envisions alignment with the China’s economic integration into the Middle Eas and acknowledges that stability in the Middle East is critical for safeguarding China’s investments and interests in the region. In this sense, the GSI serves as a practical framework—more than just an ideological concept—to protect China’s interests while fostering regional cooperation.

However, this connection may lead to skepticism. China’s push for deeper security ties as primarily serves its own economic and geopolitical interests—particularly its need for stable energy supplies and its desire to expand its influence in the region. The GSI’s emphasis on sovereignty and non-interference could also limit China’s ability to address the region’s more pressing governance and humanitarian challenges. Countries in the Middle East may appreciate the economic benefits of the BRI but may question whether China’s model can offer real solutions to the region's security problems.

A Counterbalance to U.S. Influence?

The GSI might serve as a diplomatic complement, but it is unlikely to replace the U.S. as the region’s dominant security provider.

With the U.S. reducing its direct involvement in the region, particularly as it endeavors to shift its focus to the Indo-Pacific, China’s interest in the region presents an opportunity for Gulf states to diversify their security partnerships. For some, China’s diplomatic approach and economic influence offer a viable alternative to traditional Western alliances. For others, it presents an opportunity to hedge between the two powers, leveraging their competition to extract more concessions from both sides.

The GSI’s potential as a counterbalance to U.S. influence overlooks the nuances of U.S.-Middle East relations. The U.S. remains deeply entrenched in the region, not just through military presence but also through strategic priorities like counterterrorism and other forms of non-proliferation. While the GSI may function as a diplomatic counterpoint, it cannot replace the military capabilities and intelligence-sharing partnerships that the U.S. provides. Furthermore, China’s lack of military presence in the region limits its ability to address the immediate security needs of Gulf countries. In other words, Beijing’s diplomacy is a welcome inclusion, but does not offer a response if diplomacy breaks down and the states resort to violence.

The GSI’s framework also doesn’t tackle issues like asymmetric warfare or the complexities of military intervention in regional conflicts.

Conclusion: A Complicated Path Ahead

China’s Global Security Initiative presents a compelling vision for a new security framework in the Middle East—one that prioritizes cooperation, sovereignty, and peaceful dialogue. However, Beijing’s endeavor to build this framework in a region fraught with deep geopolitical tensions and long-standing rivalries is a monumental challenge.

At best, the GSI may offer a complementary security landscape that supplements existing regional and global frameworks. At worst, it risks being seen as another tool for advancing China’s economic and geopolitical agenda, without addressing the deeper structural issues that underpin regional insecurity. For the GCC and the broader Middle East, the GSI offers both opportunities and risks. Its success will ultimately depend on how effectively it can be integrated into the region’s complex and often fragmented security environment.