Mediation has become an increasingly important function of foreign policy for states with expanding interests in regions affected by protracted conflict. For China, mediation—or the offer of mediation—has emerged as a more routine feature of its diplomacy, providing a means to manage rising tensions in areas where it has identified key strategic interests. This paper examines how mediation fits into China’s broader foreign policy approach, how Beijing’s use of mediation is evolving, and what this shift reveals about its changing engagement with the world.

Methodology

This research is based on Rihla Research & Advisory’s China Global Mediation Tracker database, which compiles and categorizes Chinese mediation efforts over the past 15 years using open-source research and publicly available information. The approach combined targeted searches in Mandarin, English, and Arabic to capture a diverse set of cases across regions and conflict contexts. While the dataset provides a strong sample that reveals key patterns and trends, it does not aim to be exhaustive. Some contexts, such as Myanmar, involve a large number of subcases of mediation that are not fully captured here. Some scholars have built context-specific data sets which represent a more granular view of China’s conflict mediation in a specific context over a longer period of time. These sublevel mediation cases, where they exist, add important nuance but are not yet represented at scale in this dataset. Additionally, the concept of “mediation” in the Chinese context remains a point of scholarly debate. As a result, this paper aims to define “mediation” in ways that reflect both policy and scholarly literature, with the goal of expanding knowledge of how China defines mediation and how Chinese mediation functions as a tool of foreign policy

Defining Mediation

China’s International Cooperation Center has employed several key Mandarin terms to frame its definition of mediation, each reflecting potential dimensions of China’s state conceptualization of the practice. In his 2024 paper “Analysis of conflict levels and the effectiveness of international non-governmental organizations in conflict mediation” [冲突层级与国际非政府组织参与冲突调停的效力分析], Zhao Yiqi, a Chinese researcher focused on conflict mediation, uses three key terms to define conflict mediation. 调解 (tiáojiě) appears as the general term for mediation, describing voluntary, negotiated dispute resolution through third-party facilitation, particularly in grassroots or lower-intensity conflict contexts. 调停 (tiáotíng) is used somewhat interchangeably but tends to carry a more formal tone, often invoked when discussing structured third-party interventions aimed at managing conflict escalation. 斡旋 (wòxuán) features when the paper addresses mediation in higher-stakes or sensitive international disputes, connoting a more active role for the mediator, including proposing solutions or brokering compromises.

This framing helps illustrate how “mediation” is understood in Chinese discourse as a concept that can be both broad and flexible, while also narrow and specific, ranging from informal facilitation to structured, formal mediation. It also underscores the central importance placed on consent, context, and timing in determining when and how mediation is pursued. This breadth contributes to the wide range of scenarios that may fall under the definition of “mediation,” particularly in conflict contexts — which is the primary focus of this database.

At the leadership level, these conceptualizations are consistent with how China’s top officials articulate Beijing’s diplomatic philosophy. In his 2024 speech marking the 70th anniversary of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, Xi Jinping emphasized that China’s approach seeks to transcend “group politics” and “spheres of influence” by offering a new path for peacefully resolving international disputes. Xi underscored that China “adheres to the peaceful settlement of disputes and opposes the use of force or the threat of force in international relations,” framing this as an enduring principle of China’s foreign policy and a key contribution to international law. At the launch of the International Organization for Mediation (IOMed), Foreign Minister Wang Yi echoed this framing, emphasizing that the organization would help transcend a “‘you‑lose‑I‑win’ zero-sum mentality,” promote the amicable resolution of international disputes, and foster “harmonious international relations.”

Chinese scholars and officials point to the Saudi-Iran rapprochement as an example of successful mediation, though the primary mediators prior to Beijing’s role, Iraq and Oman, played the most consequential role in bringing and keeping Tehran and Riyadh at the table. Chinese officials also highlight the Beijing Declaration — China’s intra-Palestinian mediation between leading political parties, hosted in 2024 — as a success after the parties signed a joint declaration, even though it saw little immediate follow-through and many of the underlying political divisions persist.

When applied to China’s practice, Zhao benchmarks this evolving mediation approach as the “power of not using power” model. He describes it as a balance between refraining from interference in the internal affairs of other countries and avoiding the escalation of regional rivalries, while also leveraging extensive economic ties to maintain partnerships with competing actors. Through its Iran–Saudi mediation, for example, Beijing demonstrated flexibility in its willingness to facilitate dialogue between rivals when conditions were ripe, while preserving its image as a neutral and pragmatic interlocutor.

A Review of the Data

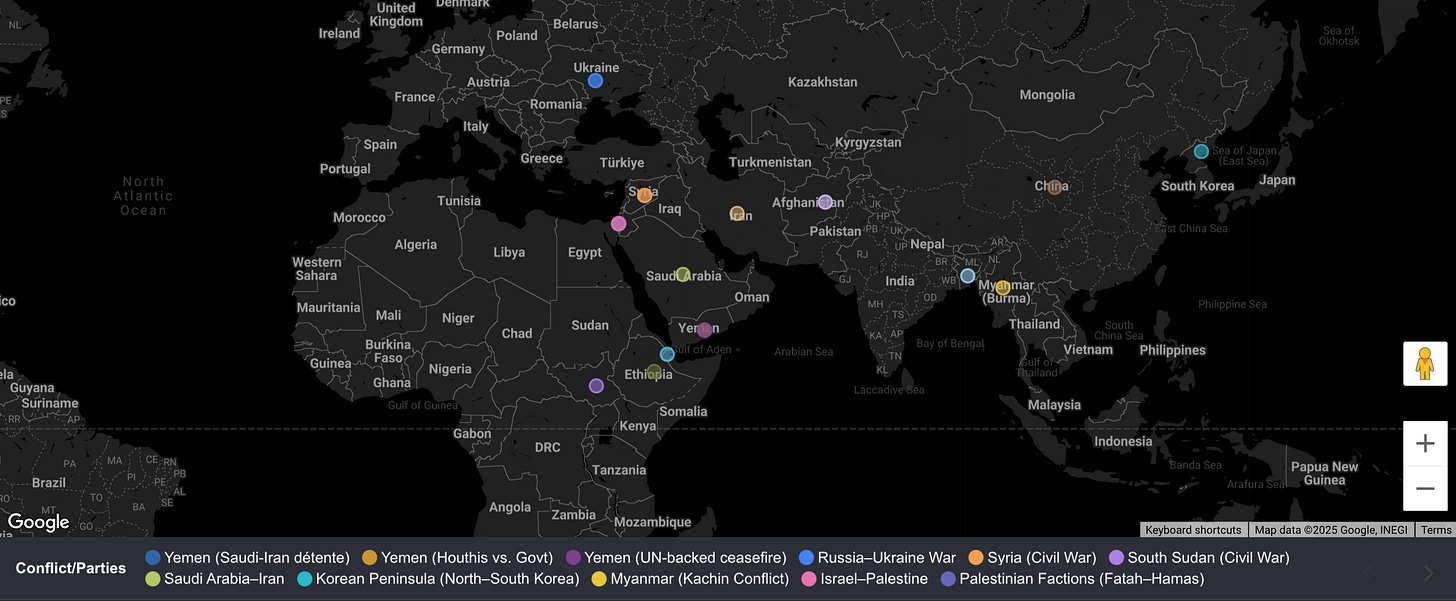

Over the past 15 years, China has steadily expanded its diplomatic portfolio to include an increasingly visible role in international mediation efforts. While China’s foreign policy tradition has long emphasized non-interference, a careful reading of its mediation engagements since 2010 reveals a growing readiness to wade into some of the world’s most intractable conflicts — from the Korean Peninsula to Yemen and Ukraine. The data enables us to do an initial exploration into the trajectory of Chinese mediation from 2010 to 2025, highlighting key trends, variation over time, geographical patterns, and what drives Beijing’s evolving approach to mediation as a tool of foreign policy.

Between 2010 and 2025, we cataloged at least 23 cases (though this is not exhaustive) of Chinese mediation offers or actions. These efforts show a clear upward trajectory over time, reflecting a larger interest in the idea of mediation and a greater sense of diplomatic confidence. Of the cases identified, we assessed approximately at least a third resulted in successful mediations (there was some form of resolution as a result of the action), about 17 percent were partial or inconclusive (there was an engagement, but no identifiable success factor could be identified), and roughly 43 percent failed or did not materialize into negotiations. These initial figures illustrate both the inherent complexity of mediation and China’s still-limited influence in conflict resolution contexts, especially when managing deep-seated rivalries or protracted conflicts.

China’s mediation activity over this period unfolded in phases. Between 2010 and 2013, China’s actions were largely tentative, framed as proposals or outreach to individual parties without robust follow-through, such as the proposed six-party talks for North–South Korea. Between 2015 and 2019, China gradually increased its engagement, with more materialized efforts such as mediation in South Sudan and outreach in Afghanistan and Yemen. This coincided with the broadening of China’s global economic footprint through the Belt and Road Initiative, including into conflict-prone areas like the Middle East which were important to China’s domestic interests. By 2020 to 2025, there was a clear intensification and formalization of mediation attempts as China gained more confidence in its ability to maneuver and balance competing rivalries, like Iran and Saudi Arabia, and still maintain its core economic interests. Notably, 2023 marked the peak year in the dataset, with four documented cases, including China’s active involvement in Middle East dialogues and renewed diplomatic posturing around the Ukraine conflict. This rising tempo reflects China’s growing sense of diplomatic confidence as a “responsible major power,” in line with Xi Jinping’s concept of “major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics.”

Geographically, China’s mediation efforts have been heavily concentrated in regions of geopolitical salience for Beijing. Of the cases we identified, about nearly half were in the Middle East and North Africa, with repeated attempts to mediate Israeli-Palestinian tensions, the Yemen conflict, and broader Gulf rivalries. South and Southeast Asia featured prominently as well, particularly Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, reflecting China’s interest in borderland stability and BRI connectivity. In Eurasia, China’s offers to mediate in the Russia–Ukraine conflict emerged from 2022 onward, signaling Beijing’s desire to project an image of itself as a mediator on the global stage, even in highly sensitive theaters.

Analyzing China’s International Mediation

A striking finding is that virtually all of the cases identified involve countries or regions where Beijing has significant geopolitical, economic, or strategic interests—whether tied to Belt and Road Initiative investments, energy corridors, trade routes, or the management of regional stability. This reflects that China’s mediation behavior is closely intertwined with its broader foreign policy priorities. The dataset suggests that China tends to direct its mediation efforts toward countries where it holds leverage through investments, economic trade, diplomatic or political ties, or perceived neutrality. In these contexts, mediation offers often materialize into at least partial engagements, although success is far from guaranteed. Rather than reflecting a clear dichotomy between “priority” and “non-priority” geographies, the data underscores that China’s mediation is concentrated in theaters that, to some degree, matter to its national interests. How China defines those interests varies is likely to vary between cases. Where China has leverage, its diplomatic overtures are more likely to lead to tangible engagements, while in areas where its influence is less direct or where conflicts involve entrenched rivalries, China’s offers often remain symbolic or aspirational.

This pattern of selective engagement is reflected in the geographic variation of China’s mediation activity and its varying levels of success across regions. While China has offered to mediate in several high-profile conflicts, the results vary significantly by region. In the Middle East, despite five documented offers to mediate between Israel and Palestine — the most for any conflict in the dataset — none materialized into substantive negotiations, underscoring China’s marginal influence over deeply entrenched, historically Western-dominated conflict resolution tracks. In contrast, China achieved greater traction in Yemen, with three documented cases and a modest record of convening parties to the table. In Africa, South Sudan stands out as one of China’s more prominent mediation moments, where both its strong energy interests and regional cooperation with the Intergovernmental Authority on Development and African Union frameworks helped produce improve the mediation outcome. In Eurasia, China attempted to position itself as a potential interlocutor on Ukraine from 2022 onward, while trying to navigate sensitivities with Russia, while avoiding direct criticism of Moscow. China’s efforts largely were unsuccessful due to the intense nature of both the conflict and the entrenched security dilemma persisting across both Ukraine and Russia, as well as the ongoing pressure from regional states, the EU, and the United States. Many looked skeptically at China’s offers due to a perception of it backing Russia, despite its invasion of Ukraine, and its condemnation of NATO as an “enabler” of the Ukraine war. Across these cases, China has often aimed to position itself as a pragmatic interlocutor by offering its good offices when diplomatic dividends are available but retreating from active follow-through when the risks outweigh the rewards.

Institutionalizing Mediation in Foreign Policy

Several factors underlie the growing shift toward more formal mediation as a tool of Chinese foreign policy. First, China’s rising diplomatic activism reflects its desire to be recognized as a co-equal global power, capable of shaping outcomes in theaters traditionally dominated by Western states. By offering to mediate, even when outcomes are uncertain, China signals its relevance and maturity as a diplomatic actor. Second, the expansion of BRI has heightened China’s exposure to regional instability. Mediation serves as a means to reduce risks to BRI projects, protect Chinese nationals abroad, and create more stable investment environments. Third, mediation enhances China’s soft power by presenting it as a neutral, non-imperial power, contrasting with Western interventionist approaches. Mediation aligns with Beijing’s narrative of “win-win cooperation” and positions it as a constructive force for peace, regardless of the actual outcomes. Finally, mediation offers often function as diplomatic hedging. It is a low-cost way to remain relevant in conflicts where China has limited leverage but seeks to preserve future options, as seen in its posture toward Ukraine and the Israel–Palestine conflict.

China’s mediation efforts have shown signs of gradual institutionalization. We observe more frequent formal statements framing China as a potential mediator, increasing references to concepts such as the Global Security Initiative and “Chinese solutions” to global conflicts, and a growing repertoire of diplomatic mechanisms, from hosting summits to issuing multi-point peace proposals like the Ukraine 12-point plan. However, China still lacks a dedicated mediation infrastructure comparable to that of countries like Norway or Switzerland. There is no Chinese equivalent of a seasoned foreign ministry peace bureau or a roster of experienced mediators ready to deploy, and the ecosystem of supporting civil society actors remains underdeveloped. But this may soon be changing as China looks to make mediation a larger part of its foreign policy.

In 2025, China took a significant step toward institutionalizing mediation as a tool of foreign policy with the launch of the International Organisation for Mediation (IOMed) in Hong Kong, the world’s first intergovernmental body dedicated exclusively to mediation. Framed as a voluntary, flexible, and non-confrontational alternative to arbitration or litigation, IOMed reflects Beijing’s ambition to shift from participant to rule-maker in global governance, particularly in the eyes of the Global South. Its design emphasizes consensual engagement: mediation is voluntary, proceedings are confidential, outcomes are non-binding unless all parties agree, and consent can be withdrawn at any time. While IOMed’s primary focus is international economic and commercial disputes, its structure leaves open the possibility that it could serve as an early dialogue forum for states wishing to avoid escalation into conflict. Member states can exempt sensitive matters like territorial sovereignty or maritime boundaries, ensuring that politically fraught disputes remain outside its reach unless both sides agree.

IOMed mirrors and institutionalizes many of the patterns that emerge from this dataset. Over the past 15 years, Chinese mediation efforts have tended to be highly selective, concentrated in contexts where Beijing holds geopolitical or economic leverage, and structured around voluntary, discreet engagements rather than binding outcomes. IOMed’s architecture codifies this cautious and flexible approach: voluntary participation, opt-out clauses, confidentiality, and non-binding results. Just as the data reveals that China’s mediation efforts have been more successful in cases where risks and stakes are low, and less effective in deeply entrenched disputes requiring credible neutrality and enforcement mechanisms, IOMed’s design makes it appealing as a platform for early-stage dialogue or non-political disputes, but less suited to mediating core sovereignty disputes or ending active conflicts. In this way, IOMed can best be understood as an effort to formalize and globalize (or regionalize to the Global South) a distinctive mediation model that has characterized Beijing’s foreign policy behavior to date.

China’s mediation track record reveals important limitations. In many regions, Beijing faces a credibility gap with many parts of the world. It’s relationships with actors like Russia or Iran undercut claims of neutrality given both are actively (or were recently) at war. That concern is amplified by China’s own track record. Some scholars point to the 2016 South China Sea arbitration under UNCLOS,. In this scenario, Beijing rejected the tribunal’s authority and contested the legality of its ruling. This precedent will raise doubts among international peers about whether China will treat IOMed as a principled mechanism or as a tool to be used selectively. Other Chinese scholars have proposed that IOMed could be the mechanism used for mediating South China Sea tensions with the Phillipines. The real evidence comes down to a track record of success. It remains too soon to tell.

Can Chinese mediation end war?

The data suggests not yet. Looking forward, Beijing’s IOMed could be applied to conflict, but it is not designed to end wars. Rather, it may find a unique niche as a dialogue forum for resolving non-economic disputes between Global South countries before they metastasize into full-blown conflict. Its success, however, will depend on China’s willingness to exert leverage to sustain negotiations when talks begin to falter. Consistent with its preference for state-to-state diplomacy, China is likely to privilege elite engagement over any meaningful inclusion of grassroots or civil society actors. And in most cases, Beijing is unlikely to apply pressure to bring or keep disputing parties at the table if political risks outweigh the strategic benefits. While the Iran-Saudi agreement is frequently held up as a breakthrough moment for Chinese mediation, most observers acknowledge that Oman and Iraq carried the bulk of the quiet, sustained mediation work over several years. China’s role was crucial in formalizing the outcome—but not in shaping the process.

More broadly, while China’s diplomatic practice is evolving, it still lacks the institutional depth and surrounding ecosystem—civil society organizations, independent think tanks, and NGOs—that have historically supported Western-led and UN peace efforts. These auxiliary actors often sustain grassroots engagement, maintain pressure for follow-through, and reinforce peacebuilding from the bottom up. Where China is unlikely to use leverage, these actors can often create the bottom-up pressure needed to keep negotiations alive and push for resolution. In their absence, Beijing’s top-down model risks faltering once state-level dialogue stalls or loses momentum.

The coming years will test whether China can translate its mediation offers into durable diplomatic institutions and real results.

Note: All percentages and shares cited refer specifically to the cases identified in this dataset and do not necessarily reflect an exhaustive record of all Chinese mediation efforts globally. Please see the The China Global Mediation Tracker to access the data.